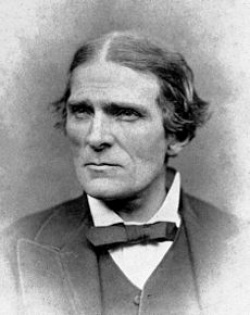

Sir John Scott Burdon-Sanderson

- Born

- 21 December 1828

- Died

- 23 November 1905 (age 76)

Sir John Scott Burdon-Sanderson was a British physiologist and a pioneer in electrophysiology. As is with the nature of science, it can sometimes be embroiled in controversy. Burdon-Sanderson seemed to experience more than his fair share due to his views on animal testing.

After being educated in Edinburgh and Paris he moved to London to become a physician. While working through the mid 1800s, England was hit with a number of debilitating and life-threatening diseases. Burdon-Sanderson dedicated much of his time to investigating the outbreaks of diphtheria and cholera, generating a number of studies and vast quantities of important data about these diseases.

Some years later, Burdon-Sanderson made an observation that would change the course of medicine forever. When one thinks of antibiotics, and in particular penicillin, the name that usually comes to mind is Alexander Fleming. However, in 1871 Burdon-Sanderson described how bacterial growth is inhibited when exposed to penicillin. This observation was made 57 years before Fleming made his discoveries, making Burdon-Sanderson a truly outstanding, but sometimes forgotten scientist.

It was when he moved to the University of Oxford that the aforementioned controversies really began. He was appointed as the first ever person to hold the Waynflete Chair of Physiology and a proposition was made to provide him with a large laboratory and lecture rooms to carry out his work. This was met with a huge clash from the anti-vivisection movement who oppose the use of animals in scientific research.

Many believed that the huge sum of money being spent on a man who advocated the needfulness and usefulness of experimenting on animals was a travesty. However, despite all the protests it was voted by an extremely tight margin that he would be allowed the laboratory and lecture rooms, and in the same year he also received the Royal Medal from the Royal Society.

While he was still met with a number of opponents on the grounds of animal testing later in life, he still managed to have a distinguished and successful career until his death in 1905. He was a lecturer to the Royal College of Physicians, served on three Royal Commissions, and was the president of the British Association (Nottingham).