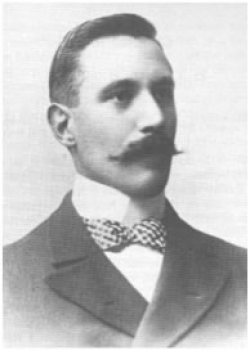

Charles Chamberlain Hurst

- Born

- Unknown

Charles Chamberlain Hurst was an English geneticist who was one of the early explorers of the science of genetics. Famous for his early investigations into plant hybridisation, the process of cross-pollinating different species of flora, and his study’s of eye colour inheritance. He was seen as one of the founding contributors to the scientific community’s acceptance of Mendelian’s theory of genetics in Britain. He lived from 1870-1947.

Born in 1870, Hurst was brought up by a family working in horticulture, his family owned a nursery in Burbage Leicestershire. As a young scientist he aspired to study the Natural Sciences within the prestigious halls of Cambridge but due to illness found an alternative route into academia. He began much of his research into genetics at the family nurseries in Burbage, after inheriting the business he created a laboratory where he could observe the results of cross-pollinating between the wonderful orchids grown on the premises.

Hurst's close inspection and documentation of the results of hybridisation, ultimately led him to publish papers, such as, ‘The Curiosities of Orchid Breeding’ in 1898, in which he states his vision that hybridisation was responsible for the evolution of new species. He noted that certain traits could be crossed in plants and the variable offspring of hybrids would stand a better chance in a challenging environment than the more uniform offspring of the parent species, which would have been adapted to old conditions. The views and hypothesis he formulated were ahead of their time and published long before other leading geneticists generated similar theories.

Whilst in Burbage Hurst probed further into the genetics of inheritance, closely examining the results of the ability to inherit certain characteristics, such as coat colour in domestic animals and eye colour in humans. Hurst’s lengthy study into inheritance saw him conclude that the genes resulting in brown colouring of the pupil were dominant to that of blue, which were a recessive trait and so stated that to possess blue eyes, you would have to inherit the gene for blue eyes off both parents.

As conditions changed, new species would be evolved more fitted to the new conditions of life than the old species, which they would gradually replace, and I venture to suggest that natural hybridisation is the most rapid of nature's means towards that end.

Charles Chamberlain Hurst, Curiosities of Orchid Breeding, 1898

Hursts’s extensive work and research saw him become more established in his field and led to collaborations with like-minded individuals, such William Bateson. Here they delved deeper into the route of inheritance and it’s role in evolution, proposing that Darwin’s theory of evolution went hand in hand with Gregor Mendel’s theory of inheritance.

Whilst many consider William Bateson to be the first British scientist to bring the theories of Mendel to Britain, it was Hurst’s detailed work in hybridisation that led to the production of strong irrepressible evidence, supporting the ideas of inheritance that made it impossible to deny.